A new leap in understanding nickel oxide superconductors

Researchers discover they contain a phase of quantum matter, known as charge density waves, that’s common in other unconventional superconductors. In other ways, though, they’re surprisingly unique.

By Glennda Chui

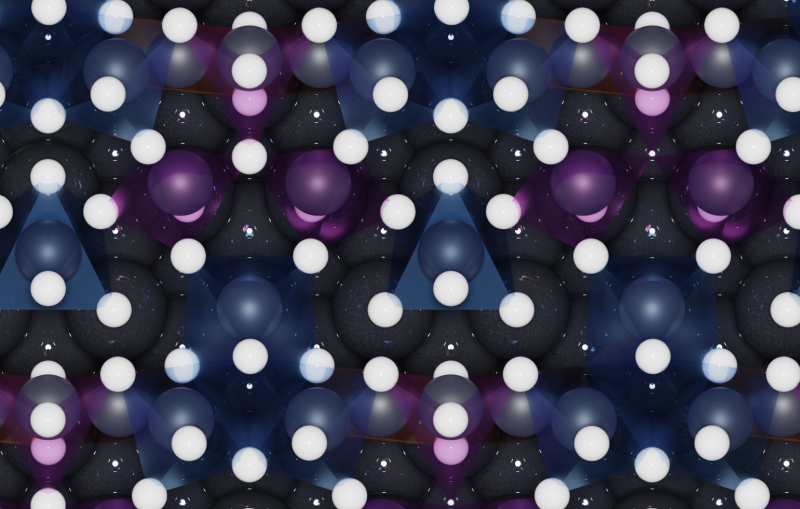

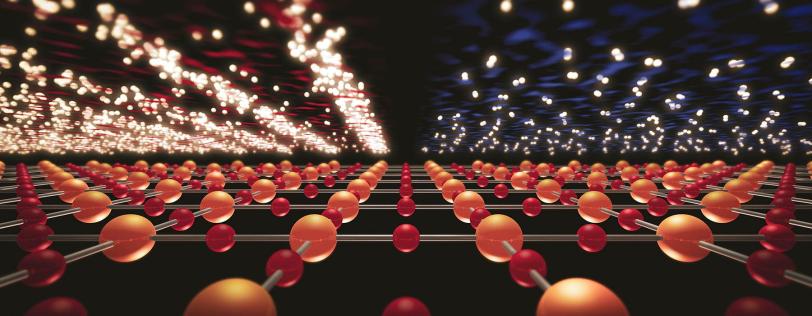

A new study shows that nickel oxide superconductors, which conduct electricity with no loss at higher temperatures than conventional superconductors do, contain a type of quantum matter called charge density waves, or CDWs, that can accompany superconductivity.

The presence of CDWs shows that these recently discovered materials, also known as nickelates, are capable of forming correlated states – “electron soups” that can host a variety of quantum phases, including superconductivity, researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University reported in Nature Physics today.

“Unlike in any other superconductor we know about, CDWs appear even before we dope the material by replacing some atoms with others to change the number of electrons that are free to move around,” said Wei-Sheng Lee, a SLAC lead scientist and investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Science (SIMES) who led the study.

“This makes the nickelates a very interesting new system – a new playground for studying unconventional superconductors.”

Nickelates and cuprates

In the 35 years since the first unconventional “high-temperature” superconductors were discovered, researchers have been racing to find one that could carry electricity with no loss at close to room temperature. This would be a revolutionary development, allowing things like perfectly efficient power lines, maglev trains and a host of other futuristic, energy-saving technologies.

But while a vigorous global research effort has pinned down many aspects of their nature and behavior, people still don’t know exactly how these materials become superconducting.

So the discovery of nickelate’s superconducting powers by SIMES investigators three years ago was exciting because it gave scientists a fresh perspective on the problem.

Since then, SIMES researchers have explored the nickelates’ electronic structure – basically the way their electrons behave – and magnetic behavior. These studies turned up important similarities and subtle differences between nickelates and the copper oxides or cuprates – the first high-temperature superconductors ever discovered and still the world record holders for high-temperature operation at everyday pressures.

Since nickel and copper sit right next to each other on the periodic table of the elements, scientists were not surprised to see a kinship there, and in fact had suspected that nickelates might make good superconductors. But it turned out to be extraordinarily difficult to construct materials with just the right characteristics.

“This is still very new,” Lee said. “People are still struggling to synthesize thin films of these materials and understand how different conditions can affect the underlying microscopic mechanisms related to superconductivity.”

Frozen electron ripples

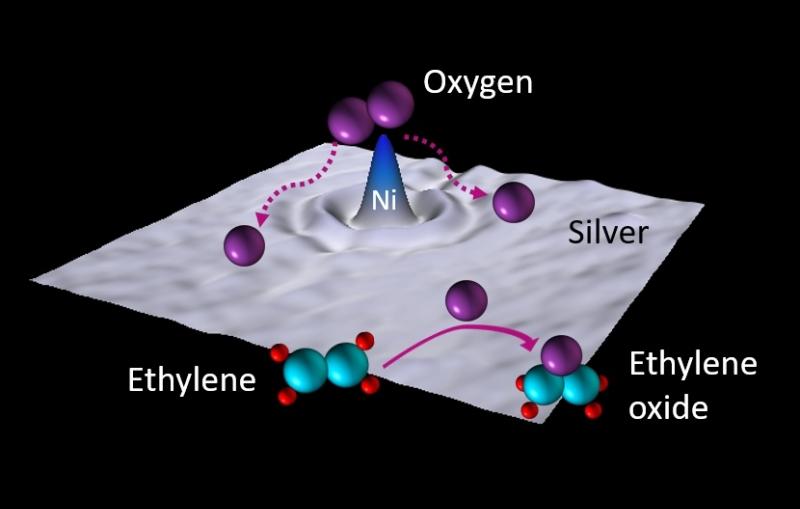

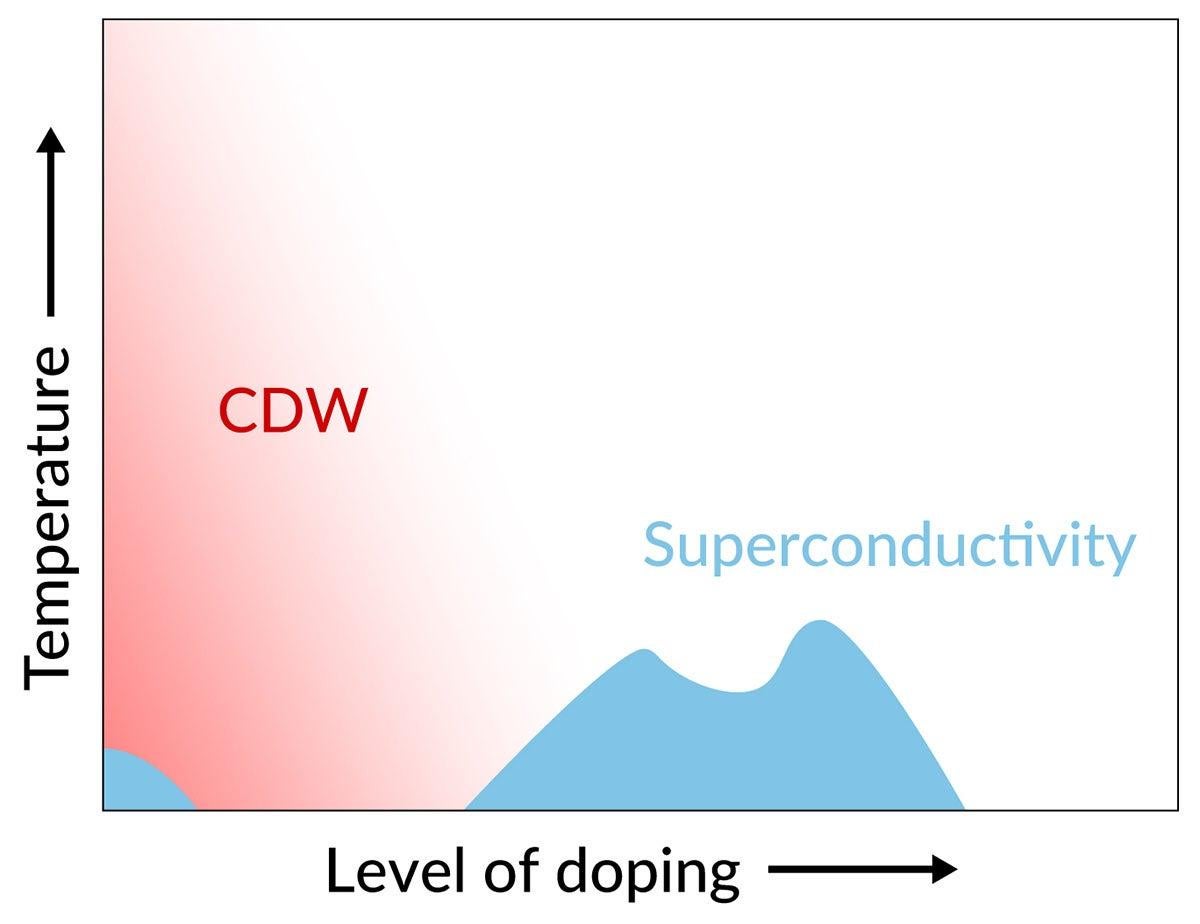

CDWs are just one of the weird states of matter that jostle for prominence in superconducting materials. You can think of them as a pattern of frozen electron ripples superimposed on the material’s atomic structure, with a higher density of electrons in the peaks of the ripples and a lower density of electrons in the troughs.

As researchers adjust the material’s temperature and level of doping, various states emerge and fade away. When conditions are just right, the material’s electrons lose their individual identities and form an electron soup, and quantum states such as superconductivity and CDWs can emerge.

An earlier study by the SIMES group did not find CDWs in nickelates that contain the rare-earth element neodymium. But in this latest study, the SIMES team created and examined a different nickelate material where neodymium was replaced with another rare-earth element, lanthanum.

“The emergence of CDWs can be very sensitive to things like strain or disorder in their surroundings, which can be tuned by using different rare-earth elements,” explained Matteo Rossi, who led the experiments while a postdoctoral researcher at SLAC.

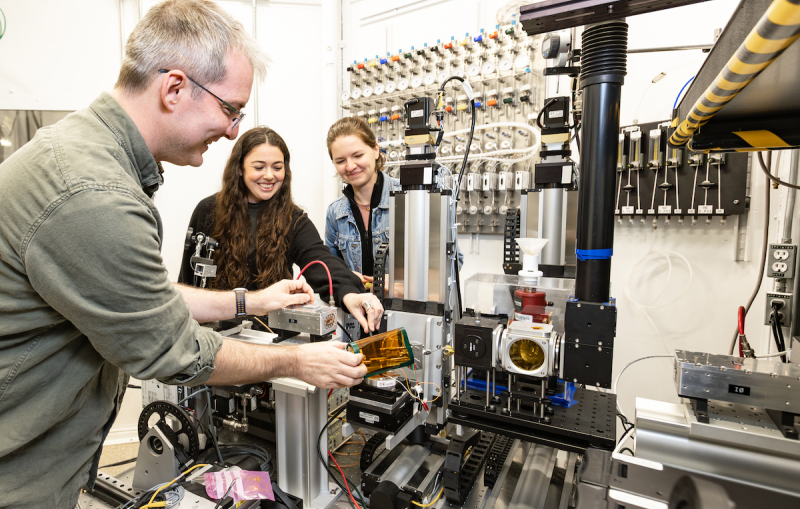

The team carried out experiments at three X-ray light sources – the Diamond Light Source in the UK, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at SLAC and the Advanced Light Source at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Each of these facilities offered specialized tools for probing and understanding the material at a fundamental level. All the experiments had to be carried out remotely because of pandemic restrictions.

‘Essentially self-doping’

The experiments showed that this nickelate could host both CDWs and superconducting states of matter – and that these states were present even before the material was doped. This was surprising, because doping is usually an essential part of getting materials to superconduct.

Lee said the fact that this nickelate is essentially self-doping makes it significantly different from the cuprates.

“This makes nickelates a very interesting new system for studying how these quantum phases compete or intertwine with each other,” he said. “And it means a lot of tools that are used to study other unconventional superconductors may be relevant to this one, too.”

Samples used in this study were synthesized in the lab of Stanford and SLAC Professor and SIMES Director Harold Hwang. Major funding came from the DOE Office of Science. Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and the Advanced Light Source are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

Citation: Matteo Rossi et al., Nature Physics, 25 July 2022 (10.1038/s41567-022-01660-6)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.